As we started to discuss in our previous article, Fate is an important concept in Tolkien’s works. Without drifting too far away from the purpose of these notes, we should remember the history of Middle-earth is deliberately reminiscent of classical epics, where the action of fate and gods influence, and ultimately determine, the action of men. At the same time, the approach used by Tolkien in his stories is both more subtle and more modern, and is influenced by his Christian Catholic ethos. Essentially, Providence acts in the World, but the action of Mortals is required for it to take full substance. The battle between good and evil is fought on a moral level, not just on the battlefield. And ultimately, there is guidance from above rewarding good deeds and sacrifices, and punishing evil-doers.

It’s not just a simplistic “Good will ultimately triumph” view. Evil can win, and win for a very long time. But, when the fight for Good is carried on in the face of all obstacles, “something” will happen to make sure a well-deserved Victory is not stolen.

Integrating such a concept in a game is not easy. When playing, we want to create a challenging and enjoyable experience, satisfying for all players, with a fair chance for anybody to win – even when playing the bad guys!

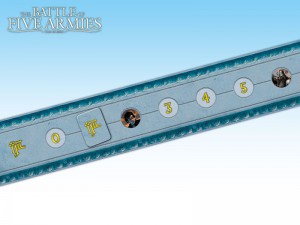

In the Battles of the Third Age (BotTA) system, this concept was represented by the Fate Track mechanic. To put it simply, the Fate Track represents a sort of “timer,” determining the end of the game. The progress of the Fate Track is not regular, but is influenced by the players’ choices. The Shadow player is racing against time – if Fate reaches the end of the Track before he can win the battle, the Free Peoples player wins the game, no matter what the Shadow achieved on the field of battle.

In the original BotTA games, the choice determining the progress of Fate was the “stance” taken by the Shadow player in each turn. The more blatant the use of the Shadow's sorcerous powers, the faster the progress on the track. To prevent a Free Peoples' victory, the Shadow player must find a balance between the all-out use of his powers, and grabbing a swift victory – or keeping a “low profile” and trying to progress toward his goal in a slower way, avoiding attracting too much the attention of the Higher Powers.

The progress of Fate is influenced by the choice, but is still non-deterministic (a common trait of all War of the Ring mechanics): the stance influences the way Fate tiles are drawn, and the draw of Fate cards – a special kind of Event card linked to Fate - but does not “guarantee” a specific outcome to the players. The workings of Fate are not completely predictable to mortals…

Initially, we started to look for an element, in the narrative of The Battle of Five Armies, which could match the role of the Sorcerous powers in BoTTA. However, no direct equivalent could be found. The battle for Rohan is strongly influenced by Saruman, and the Siege of Gondor is fought under the dark clouds of Mordor. But under the Lonely Mountain, the only “greater than human” presence is Gandalf the Wizard. The army of the Shadow may be huge, supported by hosts of bats and wargs, and led by a powerful chieftain – but no powerful Wizard lies within or behind their ranks.

After some unconvincing attempts, the solution was found. The system should be turned upside down. Instead of linking the progress of Fate to the choices of the Shadow player, we should look at what the Free Peoples player was doing. Was Gandalf wildly using his powers or – just like in the story – is he restrained in the use of magic, until the most dire moment in the battle?

By extension, we could look at the other extraordinary characters in the Battle. If the Free Peoples player makes wide use their abilities, Fate progresses slowly. If the Free Peoples player is more careful and restrained, Fate progresses faster.

The main choice determining the progress of Fate is up to the Free Peoples player – the number of Generals he activates at the beginning of a turn determines the maximum number of Fate tiles the Shadow player can draw. There is a “push your luck” element in this draw: when the Shadow player draws one tile, he may decide to stop and use it, or keep on drawing, up to the maximum number allowed. If he gets to the last tile, he’s stuck using that tile. The Fate tiles have a numeric value, and a symbol indicating whether a Fate card, a special event applied to certain Free Peoples characters (Eagles, Thorin, and Beorn), is drawn and applied or not.

Note, the progress of Fate does not just determine the end of the game, but also the timely (or untimely) arrival of several protagonists in the battle, like Beorn or the Eagles. For this reason, the set of decisions influencing the Fate track is one of the key elements in determining the flow of the battle, and the non-deterministic nature of Fate also makes sure battles are different in every game.

So, who are the Free Peoples characters who have the power to influence the progress of Fate? We will talk about them in the next article.

Follow Us on